Scan barcode

boekenzoe's review against another edition

3.0

This was a hard book to read, I'm not gonna lie. Although the story is told from third person point of view, you very much get the colonists perspective. And I have to say I don't like it one bit.

But then again, that's sort of what he wanted to achieve with this novel.

You also have to look at it as a product of its time too, I guess. In the 1930's the use of certain language was omnipresent. This 2020 translation into Dutch (the first btw) has taken that into account and has made adequate adjustments when necessary without taking away the poignancy of its original meaning.

I'm glad I read this book and I'm also glad that it made me uncomfortable, because I want to be a human before being anything else

But then again, that's sort of what he wanted to achieve with this novel.

You also have to look at it as a product of its time too, I guess. In the 1930's the use of certain language was omnipresent. This 2020 translation into Dutch (the first btw) has taken that into account and has made adequate adjustments when necessary without taking away the poignancy of its original meaning.

I'm glad I read this book and I'm also glad that it made me uncomfortable, because I want to be a human before being anything else

sjbozich's review against another edition

4.0

When I need a nice break from reading heavier things, I know I can depend on a Simenon Maigret to relax me. Short and sweet.

But CrimeReads recently had an article on his non-Maigret novels, his "serious novels". NYRofBks published a number of them in the early '00's - but they are OOP, and now sell for a premium. This was available at less than $10 as an ebook. Like most of his Maigret titles, it clocks in at less than 150 pp.

Published in 1933, as Norman Rush nicely states in his Introduction, Simenon wasn't what you would call liberal in his attitude towards African Blacks. His distaste for colonialism was not so much for the treatment of the "natives" as it was for what Africa did to the Europeans who went there.

A bit of mystery in here (there is a murder), and a nice commentary ala Joseph Conrad on what leaving civilization behind does to one, and a scathing expose on politics and justice in colonial Africa by the French. Also a nice addition to literature on French Colonialism, in the vein of Camus' "The Stranger".

For Simenon fans (although they might be disappointed in how non-Maigret this story is), but also for those interested in French Colonialism. Also hints of James M. Cain - although they do not kill off the husband. Lots of sex, but since it is 1933 mainstream publishing, no details.

3/4 out of 5.

But CrimeReads recently had an article on his non-Maigret novels, his "serious novels". NYRofBks published a number of them in the early '00's - but they are OOP, and now sell for a premium. This was available at less than $10 as an ebook. Like most of his Maigret titles, it clocks in at less than 150 pp.

Published in 1933, as Norman Rush nicely states in his Introduction, Simenon wasn't what you would call liberal in his attitude towards African Blacks. His distaste for colonialism was not so much for the treatment of the "natives" as it was for what Africa did to the Europeans who went there.

A bit of mystery in here (there is a murder), and a nice commentary ala Joseph Conrad on what leaving civilization behind does to one, and a scathing expose on politics and justice in colonial Africa by the French. Also a nice addition to literature on French Colonialism, in the vein of Camus' "The Stranger".

For Simenon fans (although they might be disappointed in how non-Maigret this story is), but also for those interested in French Colonialism. Also hints of James M. Cain - although they do not kill off the husband. Lots of sex, but since it is 1933 mainstream publishing, no details.

3/4 out of 5.

al_mutaghatris's review against another edition

3.0

It was interesting to have my opinion radically changed after reading a profile in the New Yorker about Simenon and learning what a sex-obsessed, sloppy, and prodigious of a writer he was. It made me suddenly feel no compulsion to finish reading the book.

craigt1990's review against another edition

4.0

The two things I admire most about Simenon are firstly, his restraint; secondly, his empathy.

The prose is minimalist, simple, and direct. My high school English teacher would write "more succinct" on everything I'd write-- Simenon's style is just that. The mantra is in effect tenfold here.

Events are compressed into sentence shots, more jolting than calvados and pernot. It is a very immediate style. His staccato descriptive volleys, "Lunch. A stupefying snooze. Cocktail. Dinner..." (p.52) are running starts to most scenes.

(The introduction by Norman Rush tells us that Simenon deliberately limited his vocabulary to 2000 words which demonstrates further his restraint)

As for the empathy, it's again a simple yet effective approach. Simenon tells us what the mood of a character is very bluntly. "He felt agonising impatience...He alternated between fury and despair." We are always made aware of Timar's mental state, which given his suspicions is often mutable.

Timar is a wealthy white man leaving the provinces to work at a timber camp in the African jungle. Heat is frequently mentioned. On more than one occasion the maddening heat coupled with Timar's fever leads to descriptions of feeling both "hot and cold" simultaneously.

Many things in the book are juxtaposed and given closer inspection to reveal their similarities. "The relationship between the two tones [of paint] was remarkably fine and delicate." The mask being a different shade stands out from the wall, and yet Timar examines the contrast and finds it "remarkably fine and delicate".

Timar feels homesick in this hostile environment and it's difficult for him to pinpoint his emotions. "Only the polished brass bar made him feel safe, since it was just like the ones in any provincial cafe in France." Little differences like this comfort Timar, as do the habits he forms early in the bar scenes which he has difficulty parting with.

The most memorable occasion of Simenon's exploration of the alien surroundings is when Timar is on a canoe with 12 hired colonials. The scene starts with the empathic viewpoint "Now he looked at them as human beings, trying to grasp their lives from that point of view..." What he sees is "the current carrying them on for centuries as it had carried identical canoes to the sea..." He sees it's universal. The differences are superficial: clothes, smell, sounds. Timar sees the subtle differences and how we are all really alike.

The things which differentiate us are our childhoods, upbringing and what is familiar to us. We can become slave to our routines and favour the familiar. All these differences add up for with Timar and cause conflict within. But he is at peace when he examines them and sees them to be superficial and subtle.

Which is best for rowing down an African river in a canoe, a starched white suit or a loincloth? I've read Three Men In A Boat which does actually answer that one and again it's universal - the same in Oxford as in the wilds of Africa.

Rapped up in this conflict is Timar's suspicions, card games, drinking, sex, smoking and murder and moral ambiguity of the usual Simenon noir.

The prose is minimalist, simple, and direct. My high school English teacher would write "more succinct" on everything I'd write-- Simenon's style is just that. The mantra is in effect tenfold here.

Events are compressed into sentence shots, more jolting than calvados and pernot. It is a very immediate style. His staccato descriptive volleys, "Lunch. A stupefying snooze. Cocktail. Dinner..." (p.52) are running starts to most scenes.

(The introduction by Norman Rush tells us that Simenon deliberately limited his vocabulary to 2000 words which demonstrates further his restraint)

As for the empathy, it's again a simple yet effective approach. Simenon tells us what the mood of a character is very bluntly. "He felt agonising impatience...He alternated between fury and despair." We are always made aware of Timar's mental state, which given his suspicions is often mutable.

Timar is a wealthy white man leaving the provinces to work at a timber camp in the African jungle. Heat is frequently mentioned. On more than one occasion the maddening heat coupled with Timar's fever leads to descriptions of feeling both "hot and cold" simultaneously.

Many things in the book are juxtaposed and given closer inspection to reveal their similarities. "The relationship between the two tones [of paint] was remarkably fine and delicate." The mask being a different shade stands out from the wall, and yet Timar examines the contrast and finds it "remarkably fine and delicate".

Timar feels homesick in this hostile environment and it's difficult for him to pinpoint his emotions. "Only the polished brass bar made him feel safe, since it was just like the ones in any provincial cafe in France." Little differences like this comfort Timar, as do the habits he forms early in the bar scenes which he has difficulty parting with.

The most memorable occasion of Simenon's exploration of the alien surroundings is when Timar is on a canoe with 12 hired colonials. The scene starts with the empathic viewpoint "Now he looked at them as human beings, trying to grasp their lives from that point of view..." What he sees is "the current carrying them on for centuries as it had carried identical canoes to the sea..." He sees it's universal. The differences are superficial: clothes, smell, sounds. Timar sees the subtle differences and how we are all really alike.

The things which differentiate us are our childhoods, upbringing and what is familiar to us. We can become slave to our routines and favour the familiar. All these differences add up for with Timar and cause conflict within. But he is at peace when he examines them and sees them to be superficial and subtle.

Which is best for rowing down an African river in a canoe, a starched white suit or a loincloth? I've read Three Men In A Boat which does actually answer that one and again it's universal - the same in Oxford as in the wilds of Africa.

Rapped up in this conflict is Timar's suspicions, card games, drinking, sex, smoking and murder and moral ambiguity of the usual Simenon noir.

glenncolerussell's review against another edition

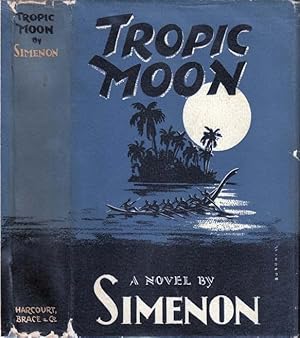

Tropic Moon - Georges Simenon’s first novel set outside Europe, one of what the author termed his romans durs, hard novels, but with Tropic Moon, not only is the story tough on the main character but also tough on the entire French colonial system, or more precisely, brutally tough on the French colonialists in Africa.

It’s 1933 and we’re in Gabon, West Africa, right along the equator in the ramshackle coast town of Liberville. We follow Joseph Timar, age 24, full of courage and enthusiasm, recently arrived from France to take up a post in the large timber company, a position he secured through his influential uncle.

Timar learns his job overseeing the cutting of timber ten days boat journey upriver will be postponed for at least a month since the company barge's damaged hull needs serious repair.

Timar resigns himself to booking a room at the one and only Liberville hotel and hanging out in the main room on the first floor that serves as lounge, bar and restaurant where all the European bachelors take their meals. Timar drinks his first shot of whisky.

All this is new to Timar - he was never accustomed to washing in a basin the size of a soup plate and going outside to squat behind a tree when he needed to take a dump. Nor had he ever shared his room with swarms of flies, mosquitoes, scorpions, spiders and other noxious insects.

And the suffocating heat and humidity. Damn! Timar wakes up completely naked the next morning in his cocoon of mosquito netting. Oh, yes, since he was drenched in sweat last night he took off his pajamas.

Suddenly, there's an attractive woman in her thirties beside his bed asking him if he would like coffee, tea or chocolate. Turns out, a husband and wife own the hotel and the woman is wife Adèle. Timar is aroused by Adèle's sensual, soft, yielding body. They have sex.

Since he had nothing to do outside the hotel, Timar remained inside, drinking whiskey, reading the newspaper and taking practice shots at the pool table. Man, the heat - all you had to do was raise an arm and you started sweating. Adèle acted a bartender and her big, fat husband Eugène occasionally made an appearance.

Then the big "gala" night had come, the entertainer, Manuelo, a female impersonator and dancer. Many European men and women fill the main room; in the darkness, hundreds of blacks peer in through the door and windows. Champagne and whiskey all round. Timar overhears an older European explaining to a young, vulgar guy how to horsewhip a black man without leaving any marks.

Just then Timar catches a glimpse of Adèle in the kitchen punching one of her employees, a black named Thomas. Thomas doesn't flinch or budge; he simply takes the blows.

Sometime thereafter, having imbibed much liquor, Timar leaves the hotel through the back door for a stroll out by an open field. Everything is pitch dark and someone comes rushing toward him. Ah, Adèle! "Get out of my way, you fool!" she tells him.

Back in the main room, having taken a seat and drinking a nightcap, Timar watches as the party winds up when two events occur in rapid succession: prior to trudging upstairs to his bed, Eugène tells Adèle to call a doctor since he has the blackwater again and this time it means he's a goner. Secondly, a group of blacks run toward the door; one of the timber traders translates their message: they found Thomas in a field, shot dead with a revolver.

Thus Simenon concludes his first chapter, creating the foundation for a series of events propelling the tale's drama. I purposely focused on the author's setup in some detail for the following reasons:

1) Simenon places Joseph Timar at the story's center and three things overwhelm Timar in French Equatorial Africa: the oppressive heat, his continual drinking and Adèle;

2) Simenon writes here about the French imperialists in action, how these French men and women are reduced to their most basic animal appetites in the sweltering heat. The novel's atmosphere counts for so much;

3) Beginning in the second chapter, Simenon's intriguing page-turner takes a number of unexpected twists and gyrations. As reviewer, I wouldn't want to divulge too much so as to spoil for a reader.

Reflect on Georges Simenon writing all those many Inspector Maigret novels. One reality stands out above all others: the need to work toward a sense of justice - if someone commits a crime, by law the criminal must be punished.

But did Simenon encounter such a sense of justice when he traveled through French Equatorial Africa? Or, rather, did these white French colonialists strongarm the native blacks into submitting to one fiercely maintained ironclad rule: whites can do whatever they want to blacks.

Sound harsh? Sound brutal? Sound like Thomas Hobbes? Young Joseph Timor voices his verdict.

I encourage you to read Tropic Moon in the New York Review Books edition where Norman Rush writes an insightful introductory essay on Simenon's African Trio - the three novels included: Talatala, Tropic Moon and Aboard the Aquitaine, brilliant translation of Tropic Moon complements of Stuart Gilbert.

Georges Simenon age 30 in 1933, the year of publication of Tropic Moon

jacquet_mipa's review against another edition

challenging

dark

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? A mix

- Strong character development? No

- Loveable characters? No

- Diverse cast of characters? It's complicated

- Flaws of characters a main focus? Yes

2.5

tristansreadingmania's review against another edition

4.0

A deliciously compressed little colonial nightmare. Less apocalyptic in tone than that other- more culturally entrenched - literary work of anti-colonialism Heart of Darkness, but infinitely more insidious. One can almost sense the moral and physical putrefaction rise from the pages, slowly invading the system like a tropical fever.

My first of Simenon's romans durs, and it won't be the last.

My first of Simenon's romans durs, and it won't be the last.

karinlib's review against another edition

3.0

A young Frenchman goes to Gabon (a French Colony in the 30s)to work in his family's company. He reaches Libreville, but is prevented from going further into the interior where the factory is located (at first) The book reminds me of Paul Bowles [b:The Sheltering Sky|243598|The Sheltering Sky|Paul Bowles|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1347986956s/243598.jpg|2287950], where foreigners are irrevocably changed by spending time in Africa (in a bad way). What bothered me about the book is that he didn't care about the locals much, in fact didn't seem to really notice them.

tarp's review against another edition

challenging

dark

tense

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? Plot

- Strong character development? It's complicated

- Loveable characters? No

- Diverse cast of characters? No

- Flaws of characters a main focus? Yes

3.75