Scan barcode

A review by seanquistador

The Enchanted Castle by E. Nesbit

3.0

Not as riddled with commentary and digressions as Peter Pan and not as thin as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (two books I appreciate for their place in child fantasy history, and continue trying, but failing, to finish), but somewhere in the middle. The middle is not necessarily a good place to be, depending on your surroundings. Sitting between a sweaty man and a screaming child on a cramped subway car is not an ideal location. I'm sure both have fans and for some the halfway point between the two would be a delectable assault on the senses (screaming sweaty man?). Not in my case, I'm afraid.

According to the afterword the book did break new ground--it was the first to introduce fantasy aspects in the Real World rather than transporting characters to a different, magical land, as in the case of both Peter Pan and Dorothy Gale. So, if you're an urban fantasy fan looking for an opportunity to do some archaeological research on the root of your Harry Dresden fandom: Dig Here. A word of caution, though, as with most digging in dirt, you may find yourself numbed by the effort before you find anything of value.

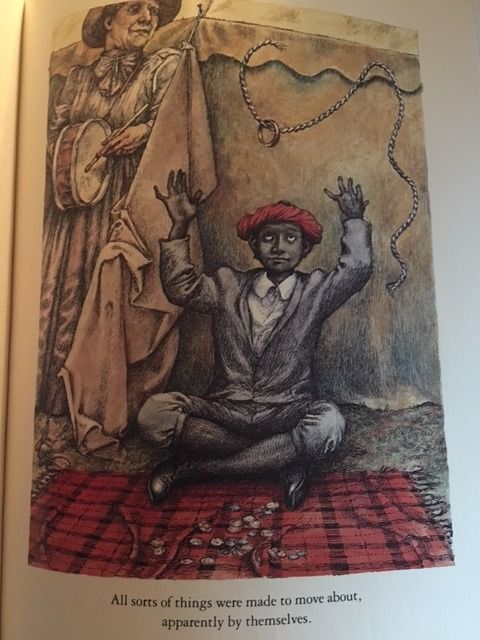

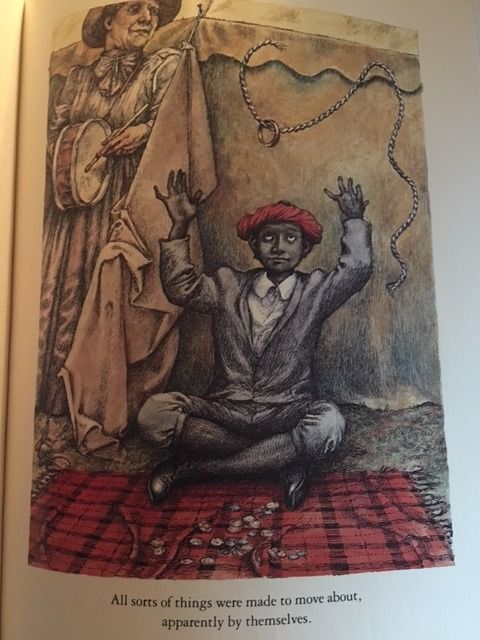

This book proved a slog. Even as a childish adult, I had a difficult time relating to the characters, and in many cases had trouble sympathizing with them, even though the author did not. The plot meandered along without much in the way of overall direction, so I had little to look forward to or expect. There were few events I found eyebrow-raising, considering this was a magical fantasy--most proved anti-climactic and resolved of their own accord. The most jarring moment of the story proved to be an episode in which a character smeared themselves with grease to appear Indian--which would probably be... frowned upon today... and a disguise I didn't expect any observers to find convincing. The writing was fairly tight, though I found the intrusions of the narrator more distracting than entertaining.

Of all the scenes they might have chosen to illustrate, this...

Most frustrating was the absence of explanation for the things that seemed most significant: where the ring came from, from who did it come, how was it enchanted, on and on along that thread. The most information they can gather is that its enchantments work in increments of seven hours. Not until the very end do these questions begin to be answered. Until then we are forced to follow the children as the try to unwind every predicament in which they entangle themselves because they can't stop using the word "wish" and voicing absurd thoughts as they're holding it ("I wish I was invisible", "I wish I was tall", "I wish these mockup people were real", "I wish I was old and wealthy", etc.).

The book is very 19th-century, upper class English, meaning much of the awe of the story might come from the children having minor adventures outside of eating and behaving properly. These particular children are obsessed with meals or, at the very least, the narrator was. The book covers several days and I don't think Nesbit missed an opportunity to describe a meal, or preface a meal through the childrens' hunger or excitement about food, or the prospect that they might buy treats, or the possibility of the baker showing up at the door at random.

There's a rule that you're not supposed to do grocery shopping when you're hungry or you'll buy more than you need because your brain thinks you're going to be in this same state of hunger forever. This same rule can be applied to writing. Nesbit apparently wrote this book on an empty stomach.

What I did appreciate were Nesbit's penchant for littering the work with wry remarks supportive of the children. All of their efforts are considered worthwhile as evidenced by her tone. There is no criticism or cruelty or condescension from the narrator, though the children can prove critical of one another. When the children put on a play using household components for scenery, despite the crudeness of the production, any derision is implied as malevolent:

I look forward to trying to read this to my kids to gauge whether their reaction is different, but I'm concerned the slow-burn nature of books from this era, which have a droll rather than snappy beginning, is more appropriate for older, more patient readers, and will disenchant them before they have a chance to get into it. Nor am I sure they hold food in the same high regard as the author.

In defense of the story, given its uniqueness at the time, this was just a cautious foot in the door. As with all things, there's a slow acclimation process that must be taken before proceeding to the next step. We can't go from Jane Austen dryly discussing the viability of suitors on a fabulous Spring day to Harry Dresden battling demons in seedy downtown Chicago after dark. Well, maybe we can (we're currently working backwards, now *sigh*), but credit must be given for that first step forward into a new realm. This was it. I hope it sold well enough so Nesbit could spend the rest of her writing career well-fed.

According to the afterword the book did break new ground--it was the first to introduce fantasy aspects in the Real World rather than transporting characters to a different, magical land, as in the case of both Peter Pan and Dorothy Gale. So, if you're an urban fantasy fan looking for an opportunity to do some archaeological research on the root of your Harry Dresden fandom: Dig Here. A word of caution, though, as with most digging in dirt, you may find yourself numbed by the effort before you find anything of value.

This book proved a slog. Even as a childish adult, I had a difficult time relating to the characters, and in many cases had trouble sympathizing with them, even though the author did not. The plot meandered along without much in the way of overall direction, so I had little to look forward to or expect. There were few events I found eyebrow-raising, considering this was a magical fantasy--most proved anti-climactic and resolved of their own accord. The most jarring moment of the story proved to be an episode in which a character smeared themselves with grease to appear Indian--which would probably be... frowned upon today... and a disguise I didn't expect any observers to find convincing. The writing was fairly tight, though I found the intrusions of the narrator more distracting than entertaining.

Of all the scenes they might have chosen to illustrate, this...

Most frustrating was the absence of explanation for the things that seemed most significant: where the ring came from, from who did it come, how was it enchanted, on and on along that thread. The most information they can gather is that its enchantments work in increments of seven hours. Not until the very end do these questions begin to be answered. Until then we are forced to follow the children as the try to unwind every predicament in which they entangle themselves because they can't stop using the word "wish" and voicing absurd thoughts as they're holding it ("I wish I was invisible", "I wish I was tall", "I wish these mockup people were real", "I wish I was old and wealthy", etc.).

The book is very 19th-century, upper class English, meaning much of the awe of the story might come from the children having minor adventures outside of eating and behaving properly. These particular children are obsessed with meals or, at the very least, the narrator was. The book covers several days and I don't think Nesbit missed an opportunity to describe a meal, or preface a meal through the childrens' hunger or excitement about food, or the prospect that they might buy treats, or the possibility of the baker showing up at the door at random.

There's a rule that you're not supposed to do grocery shopping when you're hungry or you'll buy more than you need because your brain thinks you're going to be in this same state of hunger forever. This same rule can be applied to writing. Nesbit apparently wrote this book on an empty stomach.

What I did appreciate were Nesbit's penchant for littering the work with wry remarks supportive of the children. All of their efforts are considered worthwhile as evidenced by her tone. There is no criticism or cruelty or condescension from the narrator, though the children can prove critical of one another. When the children put on a play using household components for scenery, despite the crudeness of the production, any derision is implied as malevolent:

A big sheet of cardboard, bent square, with slits cut in it and a candle behind, represented, quite transparently, the domestic hearth; a round tin hat of Eliza's, supported on a stool with a night-light under it, could not have been mistaken, save by willful malice, for anything but a stove.

I look forward to trying to read this to my kids to gauge whether their reaction is different, but I'm concerned the slow-burn nature of books from this era, which have a droll rather than snappy beginning, is more appropriate for older, more patient readers, and will disenchant them before they have a chance to get into it. Nor am I sure they hold food in the same high regard as the author.

In defense of the story, given its uniqueness at the time, this was just a cautious foot in the door. As with all things, there's a slow acclimation process that must be taken before proceeding to the next step. We can't go from Jane Austen dryly discussing the viability of suitors on a fabulous Spring day to Harry Dresden battling demons in seedy downtown Chicago after dark. Well, maybe we can (we're currently working backwards, now *sigh*), but credit must be given for that first step forward into a new realm. This was it. I hope it sold well enough so Nesbit could spend the rest of her writing career well-fed.